Cow bloat is a digestive disorder where gas builds up in the rumen and reticulum and can’t escape. We’ve all felt uncomfortably bloated after a big meal, but in cattle, bloat can become serious fast. As the rumen expands, it can press on the diaphragm and make it hard for a cow to breathe.

The good news is that this dangerous condition can be prevented and effectively managed through proper diet and nutrition. Learn what causes bloat, signs to look for, treatments, prevention, and how beef and dairy cattle feed formulas affect it.

What Causes Cows to Bloat?

Bloat is caused by the microbial fermentation of feed in the rumen. As microbes break down feed, fermentation produces gases like carbon dioxide (CO₂) and methane. Normally, these gases are expelled through belching (eructation). However, cattle will bloat if the gas is trapped. It’s forage and feed quality that’s responsible for this gas production and entrapment.

Bloat causes internal pressure on the lungs and blood vessels, leading to heart failure or suffocation. It can kill ruminant animals quickly, sometimes in just under an hour, according to the University of Arkansas. Cow bloating should always be treated as urgent.

Type of Bloat: Frothy vs. Free-Gas

The two primary bloat types in cattle are frothy and free-gas bloat. While both are dangerous and have different underlying causes, diet and feed management play a major role in each type.

Frothy Bloat

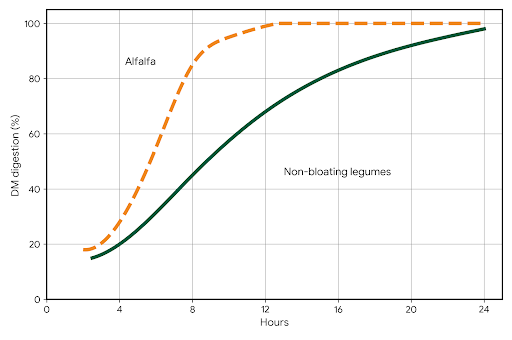

Frothy bloat, also called primary bloat, is the most common form of bloat in cattle. It occurs when fermentation gases become trapped in a stable foam within the rumen. High-protein forages that contain natural foaming agents (e.g., Alfalfa legume) often trigger foam formation. Frothy bloat can also occur in feedlot settings when rations are too finely ground or too low in effective roughage, which can increase fermentation and contribute to foam buildup.

The graph shows the association between the rise in the bloat potential of alfalfa, a high-incidence legume, and non-bloating legumes. Data source: Alberta Agriculture and Rural Development.

High-risk pastures often include legumes such as alfalfa, white clover, red clover, and sweet clover because they contain foaming agents. In feedlots, frothy bloat is more likely when diets consist of finely ground rations that trigger a surge in gas production and foamy slime from bacteria.

The problem is that cattle can’t belch out foam the way they can release a large gas bubble. Instead of joining into bigger bubbles that rise and escape, the gas stays dispersed in tiny bubbles within the foam. As more gas is produced, pressure can rise quickly. Because feed and forage conditions affect the entire group, frothy bloat often appears in multiple animals within the herd simultaneously.

Free-gas Bloat

Unlike frothy bloat, free-gas bloat traps a large free gas bubble. Instead of foam trapping tiny bubbles, something blocks or disrupts the normal belching process. Poorly processed or chewed feeds—such as potatoes, apples, turnips, or even hay twine—can obstruct the esophagus and prevent gas movement.

Other causes include vagus nerve damage, hardware disease, or thoracic abscesses. Rumen acidosis from grain overload can also reduce rumen motility and lead to free-gas bloat.

Signs of Bloat in Cattle

If you have a bloated cow, the signs are usually obvious and distinct. Pay close attention to the distended (enlarged) left side of the animal, in the rumen area. If you tap on the swelling, you’ll often hear a drum-like sound, which is a common sign of bloat.

Other signs of bloat include:

- Refusal to eat or move

- Enlargement of the entire abdomen

- Repeatedly getting up and down

- Agitation

- Becoming vocal

- Frequent urination and defecation

- Labored breathing

- Drooling

- Extending the neck and tongue protrusion in an attempt to breathe

- Rubbing their sides against trees and objects

- Distress and anxiety

- Collapsing from insufficient oxygen

- In the worst cases, death if not treated

Cow Bloat Treatment

While bloat isn’t always life-threatening, it can become an emergency quickly. Because bloat can kill a cow fast, it’s safest to treat any suspected case as urgent. Bloat can vary from mild to severe, so start by assessing how swollen the animal is and whether it’s showing signs of serious distress.

In all cases, including mild bloat, remove cattle from bloat-provoking pasture or feed.

Relieving Trapped Gas with Tubing

For severe cases, quick action is critical to help the animal release trapped gas. Michigan State University notes that a large-diameter hose or tube (about 0.75-inch diameter, or a standard garden hose) can be placed in the animal’s mouth and guided into the rumen to let gas escape. It’s critical not to push the hose into the lungs, and to move it back and forth to help access gas pockets in the rumen.

Use Non-Toxic Oils for Froth

If the gas isn’t escaping due to froth, non-toxic oils—such as vegetable or mineral oils—can be given via a stomach tube at a rate of 1.0 to 1.2 oz./100 lb. of body weight. Oils act as anti-foaming agents, helping collapse the foam so the cow can belch within 10 to 15 minutes.

Call Your Veterinarian

In severe cases, an emergency surgical rumenotomy may be required. Contact your veterinarian immediately if the animal is collapsing and can’t breathe while you’re attempting to relieve the trapped gas.

Bloat Prevention in Dairy Cows and Beef Cattle

Start with Feed Composition

Feedstuffs low in fiber and high in rapidly fermentable nutrients are the primary cause of bloat. Therefore, quality nutrition and management practices are the most effective for preventing bloat in all cattle.

Prioritize Effective Fiber and Roughage

Effective fiber stimulates saliva production, which acts as a natural antifoaming agent. Ensuring an adequate ratio of fiber and roughage to grains is critical.

Balance Ingredients, Processing, and Additives

A proper selection of cattle feed ingredients, including fiber, concentrates, feed processing, minerals, and other feed additives, is the most effective way to manage bloat and keep cattle producing safely and effectively.

Support Prevention with Consistent Intake and Grazing Management

Allowing proper time between feed intake can also help reduce the surge of rumen acidity. Proper grazing management and pasture composition (~50:50 legume-to-grass ratio) will help prevent excessive legume availability and exposure. Both are important to keep the chance of bloat as low as possible.

Use Forage Testing to Guide Your Plan

Forage testing can help you determine pasture quality, allowing your nutritionist to better guide you on bloat prevention.

Build a Long-Term Feeding Strategy

Ultimately, it’s about ensuring your cattle have access to properly balanced feed without excessive foaming agents or insufficient fiber and roughage. Likewise, formulating the diet with optimal grain sizes, grain selection, and additives will help prevent bloat and improve productivity.

Protect Your Herd Long-Term

Protect your herd from digestive issues with a science‑backed feeding plan. Star Blends will work with your nutritionists to design balanced rations that support your herd’s health, production stages, and your goals. Reach out today to customize a feed program that minimizes bloat risk and promotes long‑term health.